- What is SegWit (Segregated Witness)?

- What is SegWit?

- What was SegWit2x?

- SegWit Adoption – What’s the Progress?

- What is SegWit Account on TREZOR?

- What is a SegWit Address?

- How Does SegWit Affect Lightning Network?

- What Are SegWit Transactions? How Are They Different?

- What Does SegWit Mean?

- Is SegWit a Fork?

- Do Hardware Wallets Support SegWit?

- Who Created SegWit?

- Is SegWit Activated On Litecoin?

- How Bitcoin Transactions Worked Before and After SegWit

- How Do Blockchain Upgrades Work?

- What Are the Other Forks of Bitcoin?

- Bitcoin Unlimited

- Bitcoin Unlimited Node Chart

- Bitcoin Classic

- Bitcoin Classic Node Chart

- Bitcoin XT

- Bitcoin XT Node Chart

- Bitcoin vs Bitcoin Cash Hard Fork

- About the Author: Jordan Tuwiner

What is SegWit (Segregated Witness)?

What is SegWit?

SegWit (Segregated Witness) is the name used for an implemented process change in the way Bitcoin stores the transaction data in the blockchain. The code for this change was released in 2015, and SegWit finally went live on Bitcoin in August 2017.

SegWit improves Bitcoin and fixes a number of bugs.

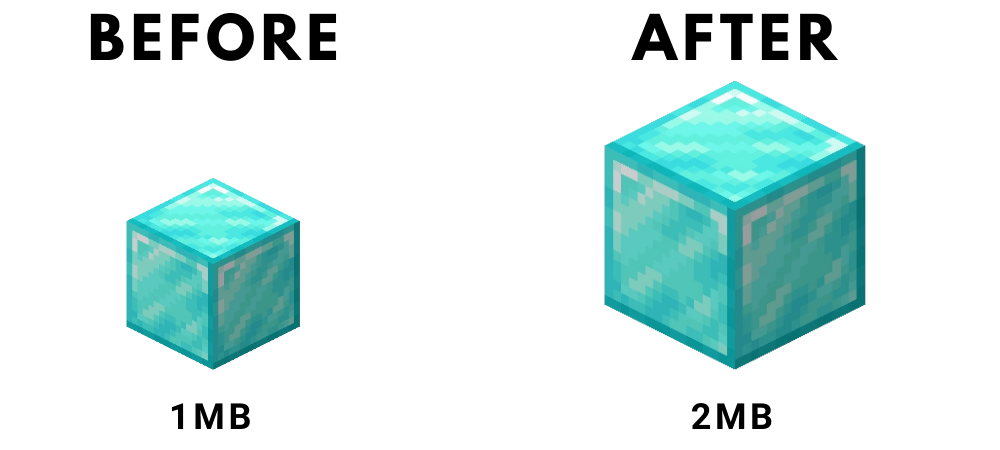

Primarily, SegWit doubled the capacity of the Bitcoin network. And while lot of people are claiming that SegWit did not increase the block size. It’s very easy to see that, yes, SegWit was a block size increase!

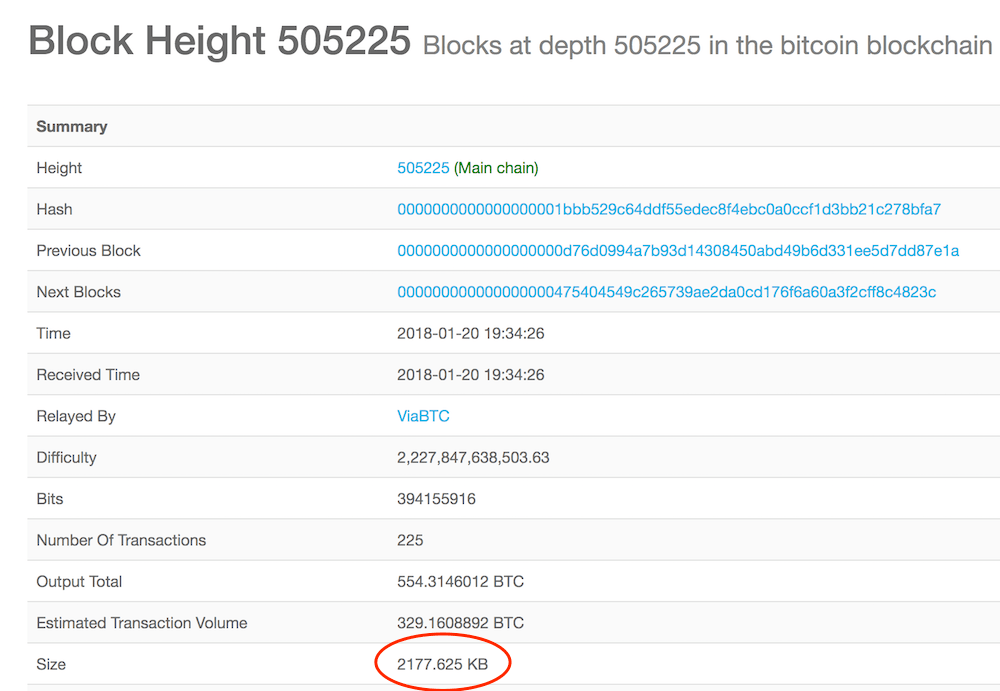

Here, for example, we can see a 2,177 KB (2.17 MB) Bitcoin block mined in January 2018.

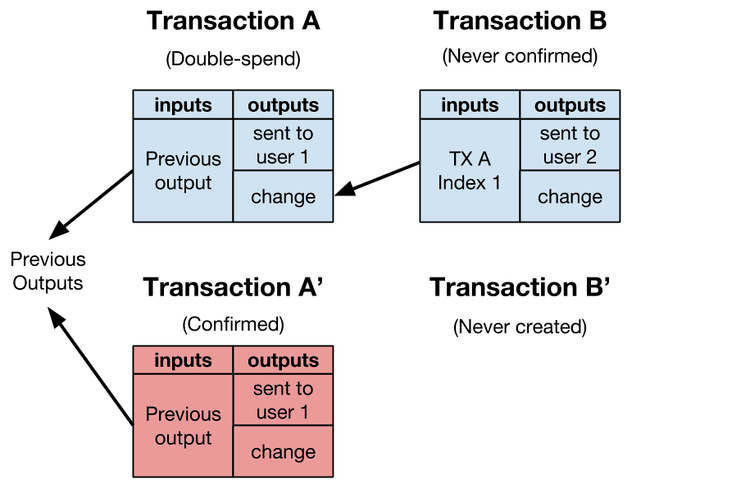

In addition to increasing Bitcoin’s ability to process transactions, SegWit fixed a flaw in Bitcoin’s protocol that allowed nodes to tamper with TXIDs of transactions on the network. This bug was known as the ‘transaction malleability bug’.

Without going into too much detail on how exactly that bug worked, here is the tl;dr:

If all the right conditions were met, a user could change the transaction ID to a spend before it could be confirmed by the network. This makes it easier to pretend this transaction didn’t happen, which may be useful to someone looking to claim they sent coins to someone else when they really didn’t.

It would be similar to receiving a package from amazon and claiming you never got it, and using a faked tracking number from Fedex that backs up your story.

That is what transaction malleability allowed you to do.

Segwit increased the amount of transactions that could fit into a block and fixed the transaction malleability bug by removing what is known as ‘the witness data’ or ‘signature data’ from the input field of a block.

Transactions get smaller, so you can put more into a block. And with witness data removed, there is no way to change the TXID of a transaction.

What was SegWit2x?

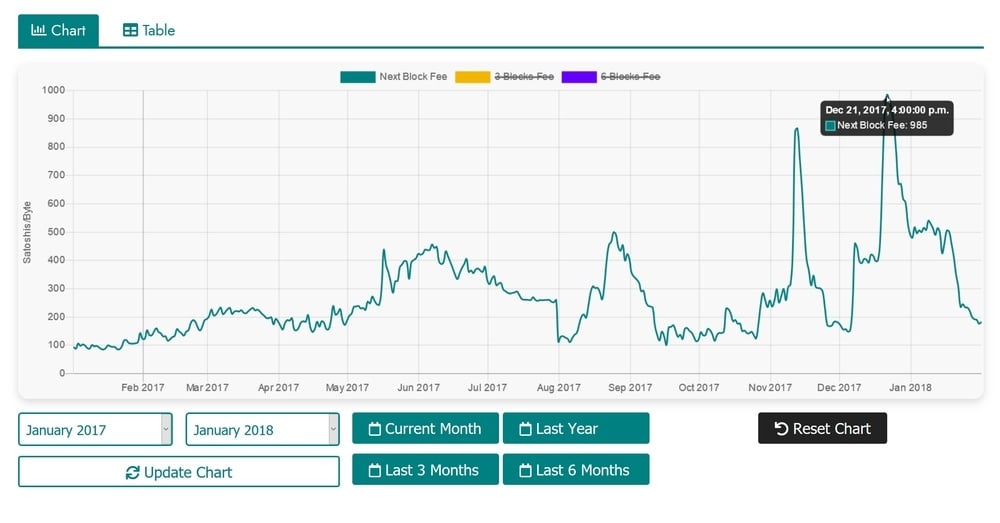

SegWit2x was a movement beyond the SegWit change to improve the Bitcoin blockchain by increasing the size of blocks from 1MB to 2MB (2x). In 2017, users had been paying miners a lot of money to make transactions. Fees were high and users were annoyed.

In fact, fees once reached nearly 1000 Satoshis per byte.

For comparison, you can normally do 1 satoshi per byte, meaning fees were 1000 times higher than normal.

Bitcoin needed to scale to service more transactions.

SegWit2x was a proposal that would require a hard fork, and it was built on the back of a soft fork proposal.

At it’s heart, SegWit2x was two separate changes to Bitcoin combined into one.

First, you have Segregated Witness or ‘SegWit’ (outlined above).

SegWit was the “small blocker” solution to scaling Bitcoin — instead of increasing the block size, you would instead use the existing block space more efficiently.

Then you had the “big blocker” solution, which is where the ‘2x’ comes from. Their solution was to simply double the size of existing blocks.

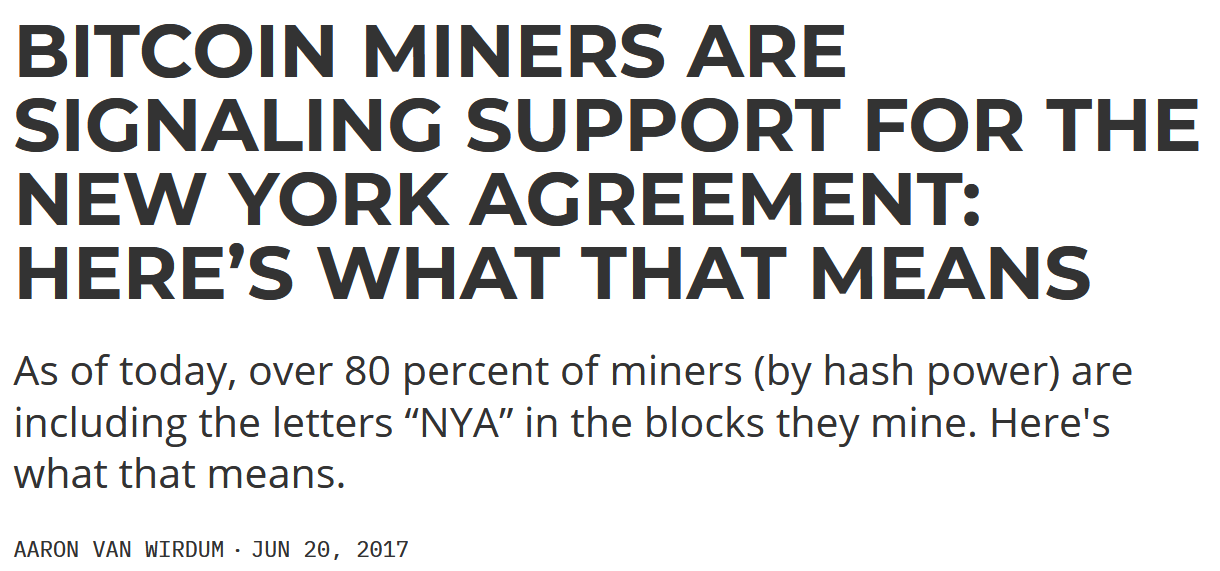

And that is where the New York Agreement came into play.

This agreement was initially formed so that the Bitcoin network would prevent splitting into two different coins.

The solution proposed by the agreement runners was to give both parties what they wanted: a doubling of the block size and an activation of SegWit.

In order to implement SegWit2x, there would have to have been a considerable change in the rules of bitcoin governance.

However, the revolutionary aim was that SegWit2x would keep all existing bitcoin users on the same singular blockchain.

In the run-up to its proposed adoption, startups and miners were the most overt supporters of the new update.

Fundamentally, this was based on the frustrations people had over bitcoin adoption. Bitcoin’s slowness allowed other coins to take market share.

The other huge fans of the SegWit2x proposal were larger bitcoin companies like Circle and Coinbase. While they would ultimately suspend their support, their logic was similar to that of miners and startups.

For the most part, these companies make money when there is lots of coin circulation. More transactions equals more fees for them to charge. If users don’t want to send their coins to your exchange because the transaction fees are too high, that is bad for business.

SegWit2X satisfied many of the shared aims of the various stakeholders. It would allow Bitcoin to increase its transaction throughput in the short term and allow exchanges and miners to continue to make money as usual even if it meant potentially harming what made Bitcoin great.

The opposition to SegWit2x came from node operators, developers, and users in developing countries.

Part of the debate came from an inherently different understanding of what matters most about Bitcoin.

For opponents of SegWit2x, decentralization was of prime importance. Doubling the block size would make it harder to run your own node and verify your own transactions and this was doubly true of people in the developing world where running a node was already relatively more expensive.

To opponents of SegWit2x, the hard fork violated the whole point of Bitcoin — to create an open financial system that everyone could afford to participate in.

Ultimately, the risks outweighed any potential benefits. While SegWit2x would increase the speed of transactions, the burden would have been felt more keenly by every day users operating nodes, as they would have had to store more data.

With opposition in both ideology and the rollout of the protocol, there was ultimately too wide a gulf to bridge.

On November 8, 2017, the proposal was suspended due to the ongoing resistance to the protocol. Companies such as Coinbase and Circle revoked their support, and ultimately the protocol failed.

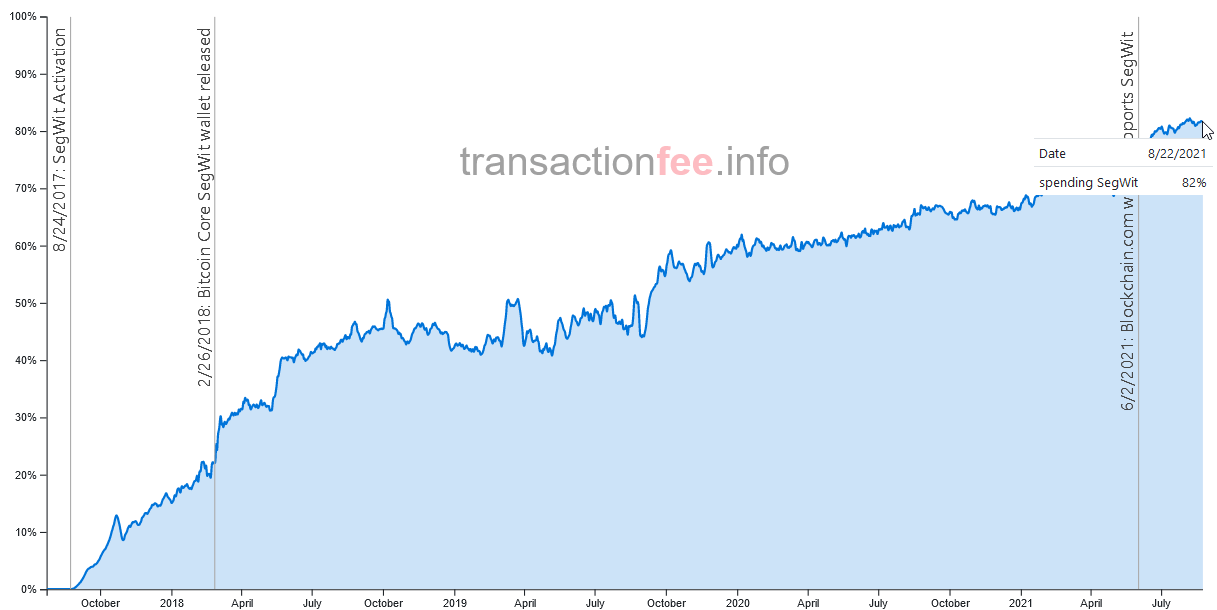

SegWit Adoption – What’s the Progress?

SegWit adoption is increasing. Nearly 71% of all Bitcoin transactions use SegWit addresses.

Another sign of the adoption is the support by many of the exchanges and digital hardware wallets allowing accounts that are SegWit accounts. Two of the top digital hardware wallets, Ledger and Trezor both support SegWit accounts, while many of the larger exchanges like Coinbase support, allow legacy and SegWit support.

It is important to understand the differences in managing these accounts on your digital wallets

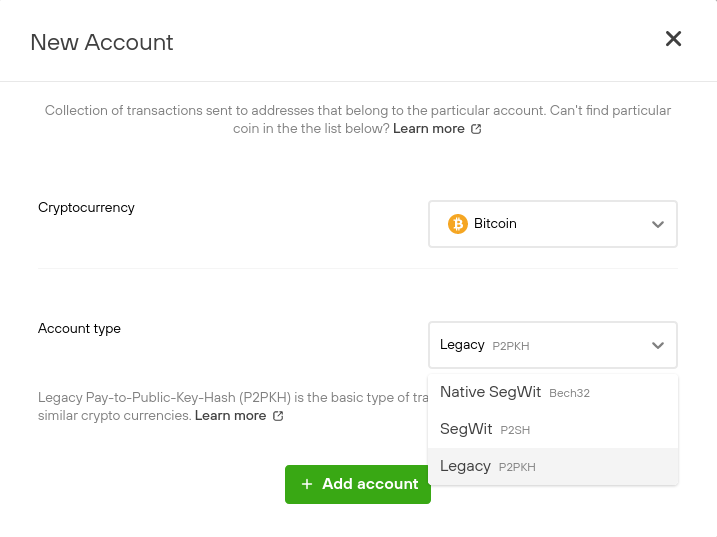

What is SegWit Account on TREZOR?

On the Trezor wallet, a “standard” account is a SegWit account. That means that when you set up a Trezor device, it will generate a SegWit Bech32 address by default.

Trezor will continue to support Legacy accounts on their devices, but in order to benefit from the SegWit change you must move your coins into a SegWit account from a legacy account.

You can pick which kind of address you want when you set up your TREZOR device:

What is a SegWit Address?

In Bitcoin there are multiple address formats that can reside in the blockchain. Most wallets support multiple format types with the most common being P2PKH, P2SH, and Bech32. The format of the SegWit address is the Bech32 format, also known as the bc1 address because the string always starts with ‘bc1’.

Here is an example of what a Bech32 address would look like:

Bech32 is the native segwit address format, and is supported by the majority of software and hardware wallets.

How Does SegWit Affect Lightning Network?

Lightening Network is a fix to both the speed and cost of a Bitcoin transaction and is a decentralized network that allows the transfer of bitcoin ownership by way of an additional layer in a transaction. SegWit is the foundation for the Lightning Network. By eliminating the possibility for transaction malleability, secure payment channels can be created that will eventually allow the Bitcoin network to process millions of transactions per second. Lastly, SegWit is a way to help Bitcoin scale to accommodate its ever-expanding user base, without forcing a hard-fork.

What Are SegWit Transactions? How Are They Different?

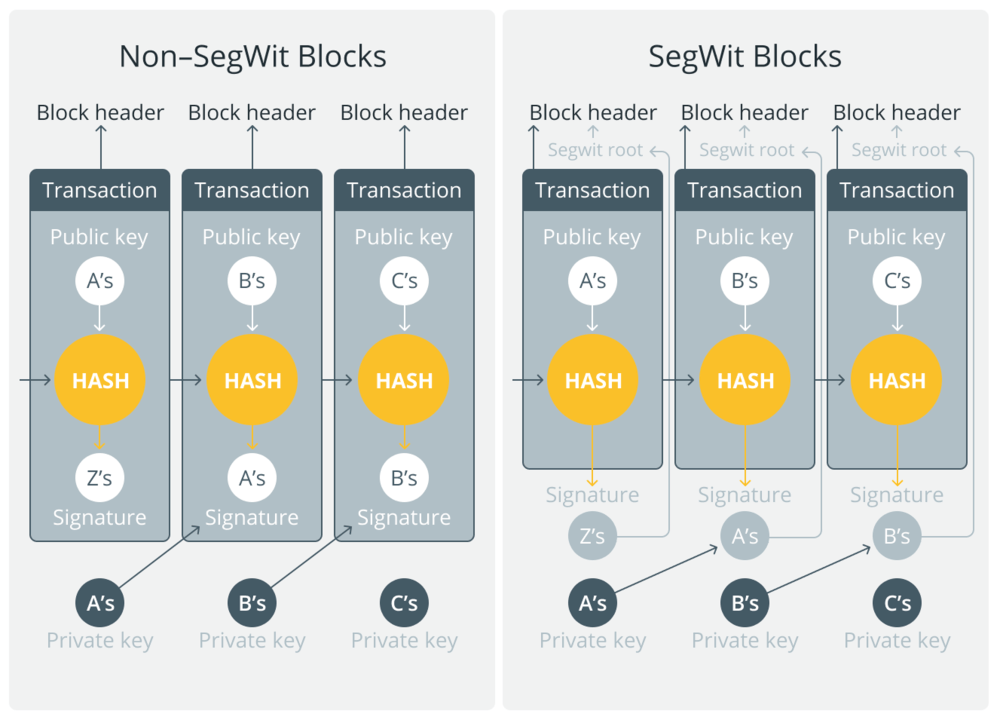

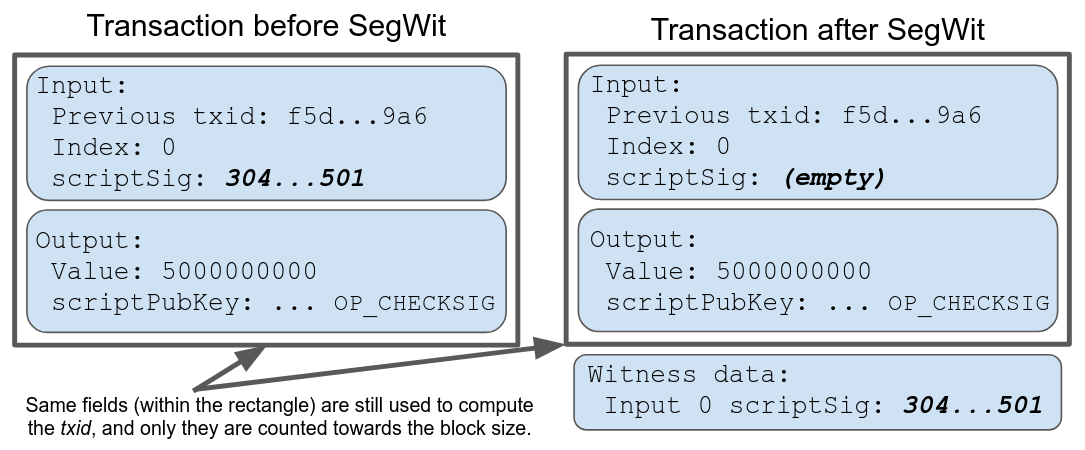

Before SegWit, the Transaction ID of a transaction could have been changed by manipulating the unlocking code of the transaction (your digital signature). After you digitally sign a transaction, it is sent through Bitcoin’s cryptographic hash function which results in a unique transaction ID.

If one character is changed in the digital signature, it will result in an entirely different transaction ID. SegWit moves the signature to the end of the transaction data, so the Transaction ID is created from everything but the digital signature.

In effect, this change renders it impossible to change the Transaction ID – if malicious nodes were able to tamper with Transaction IDs, the Lightning Network wouldn’t be possible.

What Does SegWit Mean?

SegWit is short for ‘segregated witness’.

Is SegWit a Fork?

SegWit was a soft fork. This is opposed to a hard fork which would create a separate coin (such as Bitcoin Cash). It added features and fixes to Bitcoin in 2017.

Do Hardware Wallets Support SegWit?

Yes, hardware wallets like Ledger and TREZOR support SegWit.

Who Created SegWit?

SegWit was developed by Peter Wuille. He’s one of Bitcoin’s most prolific developers, and won Coindesk’s 2017 Most Influential Award.

Is SegWit Activated On Litecoin?

Yes, congrats Litecoin! 🙂 Litecoin will also be adding more features in the future.

How Bitcoin Transactions Worked Before and After SegWit

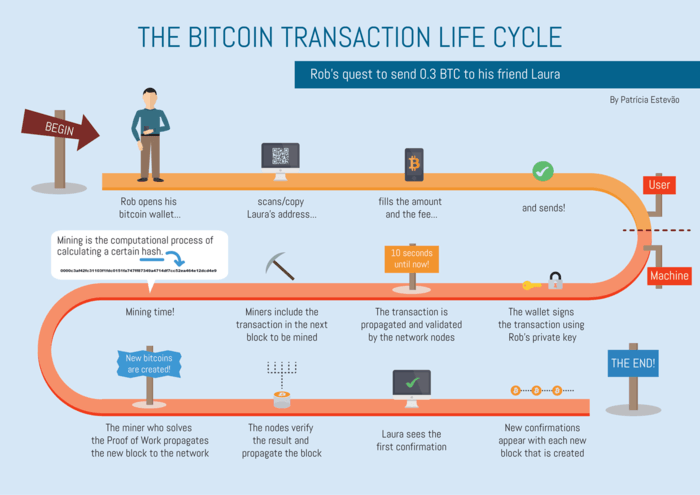

You can think of the Bitcoin (bitcoin is modeled after gold) network like a chain, and each link in the chain is a block. For the sake of simplicity, let’s picture a block that only contains one transaction. If Mike sends 1 BTC to Bob, he’d add important data to the block:

- His Input and Output

- The recipient’s public key, and the amount of BTC he is sending to Bob

- His public key

- His digital signature

Mike’s public key and digital signature must be included in the block to prove that the transaction is legitimate and really did come from him. The digital signature is included in the block as script (you can think of script as code). Just like people sign checks to authorize them, users of the BTC network must sign transactions to authorize them.

Despite being necessary to authenticate transactions, digital signatures fill up a lot of space that could otherwise be used for transaction data.

When thousands of transactions are initiated at once, there is not enough room for all of them to enter the same block. Users must pay a transaction fee which incentivizes miners to include their transaction in the block before others’. The more you pay, the faster your transaction will go through.

Unfortunately, transaction fees can get quite pricey. In December of 2017, it wasn’t unheard of to pay $50 per transaction if you wanted it to be validated within 10-20 minutes. Bitcoin’s scalability issue is one of its most significant obstacles prior to mainstream adoption. Nobody in today’s society wants to pay $20 for a cup of coffee while waiting around for their payment to clear.

Something must change.

Some believe the best way to solve the problem is expanding Bitcoin’s block size – however, that solution would require Bitcoin to hard fork. Rather than forking into a completely new cryptocurrency, SegWit has been implemented to significantly increase Bitcoin’s ability to process transactions.

For an easy primer on the lifecycle of a standard Bitcoin transaction, you can reference the image below from the Bitcoin wiki.

SegWit was activated via UASF. As mentioned previously, every block is composed of transaction data (public key, amount of BTC, etc.) and script (the sender’s public key and their digital signature). Although it is imperative that digital signatures are included in the validation process, they use a lot of space in blocks that could otherwise be used for more transactions.

Digital signatures, also known as witnesses, take up 60% of transaction data and usually the witness data exists in the middle of the transaction data. Segregated Witness is a way to remove the witness (signature) from the transaction – instead, SegWit transactions move the witness data to the end of the transaction. When a SegWit transaction is being validated by a Legacy node (one that hasn’t upgraded), the witness data is stripped from the transaction. By removing signatures from the main block of transactions, transaction size is notably smaller, thus allowing far more transactions per block.

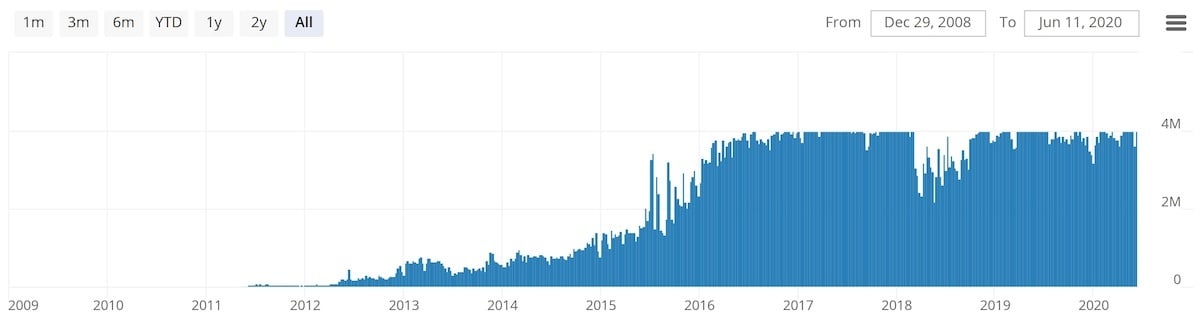

It is important to note that prior to SegWit, Bitcoin’s maximum block size was 1,000,000 bytes (1MB) – that is, once that data limit was reached, the block was no longer able to accept more transactions and any other transactions that weren’t included in the block had to wait in the mempool.

SegWit, contrary to popular belief, is indeed a block size increase. SegWit has implemented a new way to measure the size of transactions. Instead of relying on a 1,000,000-byte block size, SegWit measures blocks using something known as block weight.

Here’s the formula used to calculate block weight:

(tx size with witness data stripped) * 3 + (tx size)

Legacy transactions don’t have any witness data because it was stripped. So, the weight of a legacy transaction is effectively four times larger. SegWit transactions do have witness data, but it’s at the end of the transaction rather than being in the middle, so they are less than four times the size.

Since SegWit transactions are broadcasted to all nodes with the witness data stripped, the legacy nodes will never have to validate a block greater than 1,000,000 bytes, therefore adhering to Bitcoin’s original protocol.

Conversely, SegWit nodes can receive blocks that are very close to, but not quite 4MB in size. In order for a block to be (near) 4MB, it would have to consist of primarily witness data rather than transaction data. It would be incredibly close to 4MB with the witness data, but still, less than 1,000,000 bytes when stripped of the witness data.

Although SegWit nodes are capable of validating a 4MB (4,000,000 bytes) block, in practice, that block size is ridiculously large. In most cases, a SegWit block will not exceed 2MB.

| Before | After | |

|---|---|---|

| Max Block Size | 1 MB | 4 MB |

| Transactions per Second | 3 TX/s | 7 TX/s |

| Transaction Malleability Bug | Broken | Fixed |

How Do Blockchain Upgrades Work?

Part of the issue with SegWit2x was that it required a hard fork, as opposed to vanilla SegWit, which would only require a soft fork.

A soft fork is, at its core, backwards compatible. It allows for a shift in network rules and creates blocks that will still be recognized by existing, non-upgraded software.

On the other hand, a hard fork involves taking a blockchain and splitting it into two permanently. It performs a complete overhaul of the rules that apply to the blockchain and completely redesigns it so that it will not recognize old software.

In some cases, a hard fork can split a network into two, creating different systems that allow people to choose which they wish to adopt. This was seen in the case of bitcoin and bitcoin cash.

However, a split can also be caused if enough people adopt both possible outcomes, causing disruption to networks and systems.

What Are the Other Forks of Bitcoin?

Bitcoin Unlimited

Bitcoin Unlimited “follows the release of Bitcoin XT and Bitcoin Classic”.

XT and Classic were two previous attempted hard forks that also failed. Like Classic and XT, Unlimited is also supported by a small group of Bitcoin mining pools.

With the Remote Exploit Crash bug discovered in Bitcoin Unlimited, the proposal went down the path of failure like XT and Classic.

The Remote Exploit Crash bug was the second major bug exposed in Unlimited and caused more than 350 Bitcoin Unlimited nodes to crash instantly.

The first bug occurred when a mining pool running Unlimited mined an invalid block, resulting in the loss of 13.2 BTC.

Like Classic, many of the Bitcoin Unlimited nodes were to be fake. New Unlimited nodes popped up in massive numbers at around the same time.

Bitcoin Unlimited Node Chart

Bitcoin Classic

Bitcoin Classic was the second failed attempt to fork Bitcoin.

The proposal itself gained wide support from Bitcoin companies and a few mining pools.

Like XT, a lack of support for the proposal among the Bitcoin community as a whole led to the failure of this hard fork attempt.

Most of the Classic nodes that popped up were fake and hosted from the same ISP.

Bitcoin Classic Node Chart

Bitcoin XT

Bitcoin XT was the first unsuccessful hard fork of Bitcoin.

Led by developers Gavin Andresen and Mike Hearn, XT attempted to raise the Bitcoin block size to 8 MB.

Despite support from a few large Bitcoin companies, the proposal failed to gain enough support from the community and Bitcoin users.

Frustrated with the lack of support for XT, Hearn labeled Bitcoin a failure, quit working on the project, and sold all of his bitcoins in January 2016.

Bitcoin’s price is up more than 300% since Hearn quit.

Bitcoin XT Node Chart

Bitcoin vs Bitcoin Cash Hard Fork

Bitcoin welcomes this type of activity by being built on open-source software.

There’s been a sort of tug of war going on between Bitcoin developers since 2017, which was the main driving force behind the hard fork, ultimately leading to the creation of BCH.

The main driving force that caused this tug was the argument of how large or small each block in bitcoin’s blockchain should be.

The more conservative Bitcoin developers believed that increasing bitcoin’s block size from 1mb to 2mb was more than enough, while others argued that it was too small and wanted to expand it to 8mb, so each block could record more transactions.

A consensus could not be reached, so at bitcoin’s 478,558 block, a hard fork occurred, creating Bitcoin Cash.

About the Author: Jordan Tuwiner

Jordan Tuwiner is the founder of BuyBitcoinWorldwide.com. His work has been featured in The Guardian, International Business Times, Forbes, VentureBeat, CoinDesk and many other top Bitcoin media outlets. His articles are read by millions of people each year looking for the best way to buy Bitcoin and crypto in their country.

He has also written extensively about the history, technology, and business of the crypto world. Jordan is also the creator of some of the internet’s most famous Bitcoin pages, including The Quotable Satoshi and Bitcoin Obituaries.

To learn more about Jordan, see his full bio.

Источник